Dr. Alan Goldberg, internationally known sports psychology consultant and director of Competitive Advantage specializes in helping athletes across all sports at every level, bust slumps and overcome performance fears and blocks. Dr. G's website,http://www.competitivedge.com offers thousands of pages of FREE resources including mental toughness questionnaires for athletes, parents and coaches, articles on every aspect of coaching and parenting in youth sports, as well as a mental toughness blog.

Want Your Child to Feel and Perform Like a WINNER?

The Most Powerful 3-Letter Word a Parent or Teacher Can Use

December 11th, 2012

Kids love to announce that they’re not good at something. They usually do it just after they try something new and challenging, and they say it with finality, as if issuing a verdict.

Kids love to announce that they’re not good at something. They usually do it just after they try something new and challenging, and they say it with finality, as if issuing a verdict.

I’m not good at math!” or, “I’m not good at volleyball.”

At that moment, our normal parental/teacher/coach instinct is to fix the situation. To boost the kid up by saying something persuasive like, “Oh yes you are!” Which never works, because it puts the kid in the position of actively defending their ineptitude. It’s a lose-lose.

So here’s another idea: ignore the instinct to fix things. Don’t try to persuade. Instead, simply add the word “yet.”

You add the “yet” quietly, in a matter-of-fact tone, as if you were describing the weather or the law of gravity.

“I’m not good at math” becomes “You’re not good at math yet.”

“I’m not good at volleyball” becomes “You’re not good at volleyball yet.”

The message: Of course you’re not good — because you haven’t worked at it. But when you do, you will be good.

At first glance, it seems silly — how can just one word make a difference?

The answer has to do with the way our brains are wired to respond to self-narratives. That’s where our friend Dr. Carol Dweck and her work on mindset come in. Through a series of remarkable experiments, she’s shown how small changes in language — even a few words — can affect performance.

Her core insight is that the way we frame questions of talent matter hugely. If we put the focus on “natural ability,” kids tend to be less engaged and put forth less effort (after all, if it’s just a genetic lottery, then why should I try?). When we put the focus on effort, however, kids tend to try harder and are more engaged.

In other words, it’s all about the story, because the story creates the culture.

I happen to spend most of the year in Cleveland, Ohio, where each year the area’s teams invent new and innovative ways to lose — it’s the Silicon Valley of sports futility. Because everybody at some level (players, coaches, fans) subconsciously expects to lose. It’s a vicious cultural circle.

On the other hand, Cleveland is also home to a number of remarkable elementary and high schools that are precisely the opposite of its sports teams: strong, positive cultures where every signal is aligned with values of risk, learning, and growth. Inside the walls of these schools, it’s all about virtuous circles: feedback loops that energize and motivate.

It’s no coincidence that this “Yet” idea comes from one of these places: Laurel School, where my ninth-grade daughter happens to be enrolled. The head of school, on reading Dweck’s work, decided to make “Yet” the school’s new watchword. And in a short time, it’s caught on, traveling through the culture like a virus. Teachers are saying it. Kids are saying it. They’ve even printed it on bumper stickers (above).

Yes, it’s kinda corny, like these things tend to be. I’m sure some teens roll their eyes when they hear it. But I also think it has an effect, because “yet” tells a clear story about the value of effort and struggle, and that story is aligned with the way the brain grows.

Which makes me wonder: what other ways do you parents, teachers, and coaches tell your story and establish your cultures? Are there recurrent words/phrases – or, on the other hand, certain words that are off-limits? I’d love to hear your examples and suggestions.

Role Models of Excellence

By John Leonard, ASCA

A few weeks ago, a parent asked me what traits I looked for in a swimming coach when my children were swimming….(more than a few years ago, I might add). I found that to be a valid and important question. Here’s my answer (s).

First, the coach is going to spend more time with my son than I am. Therefore, if my son “grows up” to be like the coach, I want the coach to be a role model of excellence. Here are the things I think go into that “role modeling”.

#1. Truthfulness. You can be wrong. You can’t be dishonest.

#2. Fairness. I don’t expect everyone to be treated the same because everyone is different. But I do expect treatment of the child commensurate with the commitment of the child to the sport and team.

#3. A commitment to teaching. Both swimming skills and life skills. We’re put on earth to help one another. I want the coach to teach my son that.

#4. Hard work – In our family we believe in the importance of hard work, and that hard work is its own intrinsic reward. It’s not just Hard work= Success, it’s that hard work is rewarding all by itself.

#5. Achievement – Goal setting is important. Working towards the goal is even more important.

#6. Resilience – We all get “knocked down” by life (and sport). Getting back up every time and going back at it with no sulking is vital. We grow by defeats and our response to them, not by the “victories” in life. Cheap victories are expensive in the long run.

#7. Respect. For others work, others achievements, others effort. Learn that achievement is difficult and should be respected in every field.

#8. Respect, part two. – All human work has dignity and deserves respect. The guy collecting garbage from in front of your house in the hot south Florida sun has a heck of a hard job. Call him “sir”, mean it, and when you can, help him lift a can or two.

#9. Learning to be a learner (lifelong variety) is important to your development.

#10. Love and respect your elders. We ALL stand on the shoulders of someone and we don’t get to land on the mountain top by helicopter and think/pretend we climbed up there. Do your own climbing and respect those who gave you legs to do so. GRATEFULNESS is a wonderful quality in a person.

That’s on the top of my list. What’s on yours? I want my sons coach to be all teacher.

I was lucky to have more than one. So is your child.

All the Best, John Leonard

SUCCESSFUL PARENTING OF AN OLYMPIC CHAMPION

10/1/2012

BY CHUCK WARNER//SPECIAL CONTRIBUTOR

BY CHUCK WARNER//SPECIAL CONTRIBUTOR

This is the first in a series of themes that author Chuck Warner discovered in the research and writing of the book, …And Then They Won Gold: Stepping Stones To Swimming Excellence. Highly acclaimed by swimming leaders around the world, the book is written for swimmers, coaches and parents to learn the steps to swimming excellence.

The book chronicles the development of eight great swimmers who collectively won 28 Olympic gold medals in all four of the swimming strokes and in most distances. Their careers are chronicled from their start in swimming in summer leagues, to working their way to the top of the Olympic podium.

The swimmers are: Matt Biondi, Dave Berkoff, Mike Barrowman, Josh Davis, Lenny Krayzelburg, Ian Crocker, Grant Hackett and Aaron Peirsol.

…AND THEN THEY WON GOLD, THEME I: SUCCESSFUL PARENTING OF AN OLYMPIC CHAMPION.

- Each of these champions had parents that were very interested and supportive of their child’s sporting experience.

- For seven of the eight champions their parents coached life, not swimming.

- Their parents had high standards for the character displayed and developed by their child.

- The mothers of each of these male champions were emphasized as very important to their success.

This is a short excerpt from the chapter on eight-time Olympic gold medalist Matt Biondi with a subtitle, “A Process for Excellence.” Matt was twelve years old during this scene:

In the sport of tennis it was a common sight during televised professional matches to see the players display temper tantrums and slam their rackets. Matt gave tennis a try, and during a match he became frustrated and slammed his racket on the court. His mother didn’t say a word to him, but his match was over. Lucille [Biondi] walked out onto the court, grabbed Matt by the ear, pulled him to the car and drove him home. Matt’s exploration into choosing a sport might be his own, but the way he conducted himself as a sportsman was fully under the guidance of his parents.

For more information or to order …And Then They Won Gold, go to www.areteswim.com (access Books * Media), Swimming World Magazine or the American Swimming Coaches Association. The author is Chuck Warner, who has also written the highly regarded book Four Champions, One Gold Medal, the story of the preparation and race for the gold medal in the 1500-meter freestyle at the 1976 Montreal Olympics.

Patience - The Key to Developing the Future

Posted by Glenn Mills on Oct 24, 2012 02:26PM

When presented with hundreds of swimmers, who have hundreds if not thousands of parents watching them at each weekend competition, how do you hold back when you (and all those parents) see one swimmer with true potential? How do you hold back from pushing forward too fast?

This question is based on a specific story of two swimmers, one who matured early and one who is maturing late. Both swimmers have tall fathers, not always the best indicator, but a good indicator that each has the potential to reach the size that can get them to a higher level than they might have thought possible in the sport. As a coach, you know that physical maturation is coming. The question is: How can you convince both swimmers (and all those parents) that huge patience is needed in order for both swimmers to reach their potential? This task becomes more difficult when the early maturing swimmer is succeeding despite poor technique and stroke patterns that just aren't the ones used at the top level of the sport.

This question is based on a specific story of two swimmers, one who matured early and one who is maturing late. Both swimmers have tall fathers, not always the best indicator, but a good indicator that each has the potential to reach the size that can get them to a higher level than they might have thought possible in the sport. As a coach, you know that physical maturation is coming. The question is: How can you convince both swimmers (and all those parents) that huge patience is needed in order for both swimmers to reach their potential? This task becomes more difficult when the early maturing swimmer is succeeding despite poor technique and stroke patterns that just aren't the ones used at the top level of the sport.

The swimmer that is late in development is conscious that he is smaller than his peers, a varied population of 13-year-old boys, some who've had a massive growth spurt and some who have not. Typically, the ones dominating this age group are boys who have grown, or matured, early. Even with poor technique, because of size and strength, they can muscle their way to victory. Our late bloomer is impatient for growth, but has committed himself to improving his technique, to mastering great walls and dolphin kicks. In his favor is the fact that there is far less pressure on him from the outside environment because he's not as fast as his technique indicates.

The key to working with a late maturer is giving them praise and hope based on the skills they're developing NOW and that will be habit after they grow. If you can keep these swimmers excited about the sport, you have a winning long-term combination. The psychology and excitement of improvement makes it very easy to keep a swimmer in the sport for a long time. When improvement stagnates, so does the excitement.

The swimmer that matures early is seeing the sport from a completely different perspective. Typically these swimmers are at the top of the age-group, and are generally happy with their victories or results. They've been able to succeed to this point simply by being bigger and stronger than their competitors. The one thing we can all be certain of is that, eventually, growth stops for some, and others will catch up and even surpass the early maturers. The psychological edge and excitement factor that fuel the early developer may fade as the late developers start to grow. If and when the early developer starts to lose to some of those late developers (the kids he's always beaten), it's a very tough pill to swallow.

There will always be swimmers who are dominant from age group to senior. There will also be late-developers who hit their stride at just the right time. When the psychological and physiological development hit their peak at the same time, it's the perfect storm of long-term athletics. When the athlete is excited to train and has good technique just as the body starts to mature, massive improvement starts to take place, which typically leads to more training, more excitement, more enjoyment, and more success.

When we see an early maturer start to show promise, we look at the long-term goal and potential of the body type, the attitude, the work ethic, the parental support, and then make a decision of how to move forward. If an early development swimmer is having success with a sub-par technical stroke, it's our duty as coach to pull them back, even if that means slowing them down, to set them up for long-term success with new technique that opens a new potential for that swimmer. Early development swimmers have the ability to mask technique flaws through size and strength. The outward perception of success MUST be overcome by the knowledge a coach and staff has of what is truly a stroke with long-term potential.

To hold an athlete back, just as they're starting to show massive potential, is one of the toughest things that can be done as a coach, parent, or athlete. This is something that has to be decided upon, agreed upon, with a long-term goal and plan in place. All parties must understand that for a little while, even if it means sacrificing the trophies of a season or a year, the swimmer must take as much time as necessary to develop a stroke that gives him a new potential. By sacrificing a spec in time, he could gain a long-term career.

The coach and staff must evaluate each swimmer's stroke, technique, and attitude about the sport. Then, the swimmer, parents, and other coaches with whom the swimmer will be involved must come to an understanding that the outside world may not understand. If the swimmer displays technique that hasn't been seen at the top levels of the sport, then the "team" has to buy into the idea that training may need to be paused until technique is corrected. While great swimmers often have "signatures" or variations in technique that give them an edge, there are some absolutes in high-level swimming: streamlines, extension, ability to leverage the water, great underwater dolphins, excellent timing of strokes, and awareness of drag. While there are many ways to go about these things, the "team" must determine if the technique being shown by any young swimmer IS the technique that would be used if they were swimming at Olympic Trials or, better yet, the Olympic Games.

Not every swimmer will make it to that level. There WILL, however, be members of your team with that potential IF the "team" understands there IS potential, and evaluates each movement based on the end, rather than the present. Not ever swimmer has the potential, and while EVERY swimmer deserves to be treated in this way, not every swimmer wants to give the commitment it takes to reach their potential.

With the Olympics just ending, there is massive excitement in the sport of swimming. While some people are sitting back and enjoying the success, others are already diligently working to be (or coach) the next round of people who will participate in 2016. Others still are working toward those who will participate in 2020 and 2024.

An agreed-upon, planned approach and long-term goal of what COULD BE, has to be used every day, starting today. Do you have the patience to peer into the future and see the athlete on the blocks at Olympic Trials, with a real shot at participating in another heat?

See the future. BE the future.

“Normal People Don’t Do Deliberate Practice”

Guy Edson, ASCA Staff

First of all, there is nothing wrong with being “normal”--- it’s just that in athletics, and in scholarship, and in arts, and in business, and in charity, and in faith, and in relationships we take note of the EXTRA-ordinary person, sometimes with a bit of envy, but more often with a big smile, being happy for the person and what they have been able to accomplish. What sets apart the normal from the extra-ordinary is oftentimes the result of deliberate practice.

Psychologist K. Anders Ericsson, a professor of Psychology at Florida State University, has been a pioneer in researching deliberate practice and what it means. According to Ericsson: "People believe that because expert performance is qualitatively different from normal performance the expert performer must be endowed with characteristics qualitatively different from those of normal adults… We agree that expert performance is qualitatively different from normal performance and even that expert performers have characteristics and abilities that are qualitatively different from or at least outside the range of those of normal adults. However, we deny that these differences are immutable, that is, due to innate talent. …we argue that the differences between expert performers and normal adults reflect a life-long period of deliberate effort to improve performance in a specific domain."

“deliberate effort”

One of Ericsson's core findings is that how expert one becomes at a skill has more to do with how one practices than with merely performing a skill a large number of times. An expert breaks down the skills that are required to be expert and focuses on improving those skill chunks during practice or day-to-day activities, often paired with immediate coaching feedback.

One time I said to our senior team, “We are now going to do 39 turns and in between each turn you have about 18 yards of swimming for deliberate, and conscious thought to evaluate your turn and make an adjustment for the next one.” Most just swam a 1000 free.

Swimming is sometimes too coach dominated taking away the opportunity for the athletes to connect the dots on their own. Counsilman said, During the initial learning stage the person much use the higher centers of his brain (the cerebral cortex) to perform the movement. He literally thinks out his task.”

“THINKS OUT THE TASK.”

Over the years I have had a handful of swimmers who deliberately practiced. They often get in the water early or stay late. They try new things. They’re conscious. They show me things and they ask questions. They remind me of great basketball players who go to the gym for a few hours when no one else is around and practice deliberate hoop shooting.

Sorry to say that for most swimmers it’s just “swim a thousand free.” But for the extra-ordinary ones it’s, “39 deliberate turns, thinking and evaluating.” Ready go.”

Guy Edson has been on staff of the American Swimming Coaches Association since 1988 and is a part time swimming coach with a local club team.

THE COACH-PARENT RELATIONSHIP

BY TERRY LAUGHLIN

Originally printed in Swimming World Magazine July 1989, Adapted and used with permission of the author

Let’s take a look at the coach-parent relationship from the coach's perspective.

It can't be denied that a small percentage of those who go into coaching do so from a desire to feed an oversized ego, for the opportunity to give orders. . . and see them followed, and that such people can be high-handed, authoritarian and difficult to deal with. Other coaches start out as reasonable people, but harsh experience in parent relationships hardens them into an attitude that "It's my way or the highway."

Most coaches, though, are reasonable and responsible souls who enter the profession because coaching can offer a rewarding lifestyle.

Coaching is an opportunity to work with highly motivated, goal oriented kids-the cream of the younger generation-to inspire and teach, and ultimately to see the concrete results of your work. But to earn those rewards, you're asked to work long and unusual hours at far lower compensation than you could earn in the business world. Coaching can be lonely in a way because you give up much of the companionship of the adult world to spend so many of your hours with children; many coaches are reluctant to form friendships with parents because of the danger of criticism that you're too cozy with certain "factions." If you have a family, you spend more time with other people's kids than you do with your own.

You may become addicted, as I did, to the sense of mission you enjoy in coaching. . . . and which is lacking in other occupations; but the slings and arrows of dissatisfied parents become painful in light of the sacrifices you make for what you feel is a basically praiseworthy and selfless occupation. For many coaches, eventually the negative side of the ledger outweighs the positive side, and good, experienced coaches depart the arena for greener pastures . . . to be replaced by younger coaches who lack their maturity, wisdom and developed perspective.

What can be done about it? How can the proper and mutually beneficial trusting relationship grow between coach and parent?

The first step is for both coaches and parents to give more than lip service to the philosophy that their shared objective-and that of the entire program-is the multi-dimensional development of human potential in children. Second is for parents to make an up-front assumption that the coach does, with reasonable consistency, devote his best efforts to that end.

In such an instance, the niggling criticism will all but disappear because those objectives obviously trivialize the ordinary contentious issues such as who is selected to participate on a particular relay or start in a particular position.

Maybe what's needed is a contract to be signed between coaches and parents at the outset of their association. Here are the provisions I'd like to see in such a contract:

- I as COACH pledge to make the best interests of the children in the program the priority in my heart and mind. You as PARENT pledge to trust that my interests match your own in this common goal, though our thoughts on how it may best be attained will sometimes differ.

- I as COACH pledge to try to maintain the delicate state of balance between what may be best for the individual (your child) and the needs of the group (the team). You as PARENT pledge to remember that if on occasion your child's interest may seem to be subordinated to those of the group, in the long run the benefits of membership compensate for short-term inconvenience.

- I as COACH pledge to always communicate with you honestly, openly and in a mature manner, and to be approachable and receptive to your reasonable concerns. You as PARENT pledge to broach your concerns with me directly, in an appropriate time and place, and in a spirit of fundamental mutual interest. The PARENT also pledges to refrain from fruitless discussions of such concerns with third parties.

- I as COACH pledge my best efforts to provide your child with a range of growth experiences-some satisfying and fulfilling, others challenging and frustrating-to develop his or her ability to respond appropriately to the full spectrum of experiences in life. You as PARENT pledge to allow your child those experiences fully and completely without attempting to filter, protect or insulate the child from those that may be momentarily negative.

- I as COACH pledge to acknowledge my frailties, imperfections, my humanity, if you will, and within those constraints to strive to be consistent and fair in my dealings with team members. You as PARENT pledge to be forgiving of individual actions with which you don't completely agree, while focusing on the overall objective-that we're both working to help your child grow up to be a stronger, more self-confident and better adjusted person.

The best analogy I can think of to sum -up is that of baking a cake. Take any individual ingredient flour, baking powder, baking soda, etc., and put it on your tongue during the preparation process and you'll likely grimace at the taste. Mix them all together with care, bake at the proper temperature for the right amount of time, and serve-the result is delicious. So it is with the coach's actions.

Take any one individually-assigning a child to a remedial practice group, verbally disciplining an errant child, making a difficult and occasionally subjective decision on a relay or allowing a child to stew temporarily in the bitter fruits of some adversity-and they might be the cause for parental distemper.

But view them as part of a continuum that, balanced with timely encouragement, congratulations for good effort and the sharing of wisdom, results in the child growing and maturing, and they seem appropriate and proper. The best advice I can give to parents is to start each season with a strong commitment to support the aims of the program and the methods of the coach, and remember that commitment when you're tempted to critically examine some action of the coach out of the context of his total relationship and interaction with your child.

Reprinted from www.usaswimming.org

You Are Not Special - Because Everyone Is

The below is taken from www.huffingtonpost.com

Wellesley High School English teacher David McCullough may try to avoid clichés like the plague, but his unconventional message in his faculty speech to the Class of 2012 raised numerous eyebrows last Friday.

Instead of lauding the achievements of the graduating class — a popular tactic among commencement speakers — McCullough took the opportunity to remind the Wellesley, Ma. seniors that selflessness is the best personal quality to possess, and that “the sweetest joys of life … come only with the recognition that you’re not special, because everyone is.”

The full text comes courtesy of The Swellesley Report. Excerpt below:

“Here we are on a literal level playing field. That matters. That says something. And your ceremonial costume … shapeless, uniform, one-size-fits-all. Whether male or female, tall or short, scholar or slacker, spray-tanned prom queen or intergalactic X-Box assassin, each of you is dressed, you’ll notice, exactly the same. And your diploma … but for your name, exactly the same.All of this is as it should be, because none of you is special.

You are not special. You are not exceptional.

Contrary to what your u9 soccer trophy suggests, your glowing seventh grade report card, despite every assurance of a certain corpulent purple dinosaur, that nice Mister Rogers and your batty Aunt Sylvia, no matter how often your maternal caped crusader has swooped in to save you … you’re nothing special.”

McCullough lamented the tendency of Americans as of late to “love accolades more than genuine achievement.”

“It’s an epidemic — and in its way, not even dear old Wellesley High is immune … one of the best of the 37,000 nationwide, Wellesley High School … where good is no longer good enough, where a B is the new C, and the midlevel curriculum is called Advanced College Placement. And I hope you caught me when I said “one of the best.” I said “one of the best” so we can feel better about ourselves, so we can bask in a little easy distinction, however vague and unverifiable, and count ourselves among the elite, whoever they might be, and enjoy a perceived leg up on the perceived competition. But the phrase defies logic. By definition there can be only one best. You’re it or you’re not.”McCullough urged the Class of 2012 not to just do things for the sake of personal accomplishment or self-indulgence, but because “you love it and believe in its importance.”

This isn’t the first time McCullough’s commencement remarks have made news. In 2006, he was remembered for telling then-graduating Wellesley students to “carpe the heck out of every diem” — a signature line he alluded to in his 2012 address.

An interview with McCullough taken from www.wbur.org

Sacha Pfeiffer: What message did you want to get across to the kids? Was this intended to be a harsh message?

I wouldn’t call it harsh, no. I hoped it was realistic. Several people who have taken lines out of context –the sensationalizers and carnival barkers who are looking for a sound bite to exploit for ratings purposes — seized on that “you’re not special.” I hoped that pointing out that they’re not exceptional, they’re not special, would be liberating for them. If children are treated like they’re special, there is an implication, particularly from demanding parents, of expectation. Don’t you know you’re special? That means you should be achieving more than you are. And that expectation pressures kids, and that pressure makes them conservative and safe and unwilling to take chances. And that, in my view, inhibits their capacities or the possibility of growth.

You talked about some lines being taken out of context. And the line that is most often quoted is, “You’re not special.” Of course, what comes after that is, “Everyone is special.”

Of course. Of course.

But what do you mean by that? That everyone is special?

That everyone deserves to be treated with respect and taken seriously and cared about. Everyone on the planet. If everyone is special, then it kind of nullifies the concept of specialness. I wanted to emphasize for them that though you may have been the valedictorian, though you may have been a touchdown hero, that doesn’t make you a more important person. And when I sit and I look at my students in my classroom, each one of them is as important to me as any of the others.

There’s a point in your speech where you said: “If everyone gets a trophy, trophies become meaningless. We Americans, to our detriment, have come to love accolades more than genuine achievement.” Would you pick up a little bit after that?

No longer is it how you play the game. No longer is it even whether you even win, or lose, or learn, or grow or enjoy yourself doing it. Now it’s, ‘So what does this get me?’ As a consequence, we cheapen worthy endeavors, and building a Guatemalan medical clinic becomes more about the application to Bowdoin than the well-being of Guatemalans. It’s an epidemic. And in its way, not even dear old Wellesley High is immune. One of the best of the 37,000 nationwide, Wellesley High School — where good is no longer good enough, where a B is the new C, and the mid-level curriculum is called Advanced College Placement.

So this gets at the idea that at the most elite colleges, it’s not even great grades that are enough. You just need to be a knock-out student with ridiculous extracurricular activities.

That’s the perception, certainly. And so kids and their loving, well-meaning, ambitious parents want very much for their kids to have access to the best, and so they schedule them up to the earlobes and they demand from them extraordinary achievement in everything they do, and suddenly any capacity for self-determination or experimentation or failure goes right out the window. I try to tell my students that the only adult to whom they owe anything, really, is the adult they’re going to become. And they shouldn’t want that person to look back at them and shake his or head and say, “Oh, jeez. You blew it. You should have been thinking differently.”

So in many ways this is as much or more a critique of parents, it seems, than of students and kids.

And I’m one of those parents, and so I know whereof I speak. I say all of these things in sympathy with these parents. I feel, too, the same cultural encouragements, the same pressures, the same desire to see my kids have access to the best education available to them, the best experience. And I don’t know what to do about it! I’m trying, I’m thinking, and maybe this speech of mine might encourage conversation, which might inspire some change.

Aerobic Development - Guide for Parents

John Leonard

Otherwise known as basic aerobic fitness....how is it developed in Swimming? We use a training formula for this quality that is time tested and proven over the past 60-70 years. What we want to do, as one quality of athletic development, is to make young athletes "more fit" than they were prior to training.

Another simple definition is the ability to do more work, faster and for longer than previously.

First, we increase the distance swum.....long, slow, easy swimming. Some of our swimmers are not able to complete a full easy 1000 of free and "hold steady the splits" (intermediate 100 times). Others can handle a 500 now and some, alas, cannot yet handle a 200 capably. That's the first step. (Truly fit swimmer can handle a straight 3000 free with steady splits.)

Second, we swim some shorter repeats and try to reproduce slightly faster times than on the long, slow swim. So perhaps we swim 10 x 100 free on 1:40 (1 minute and 40 seconds). Some get 30 seconds rest, some get 10. The faster you swim, the more rest you get. So, step two, is being able to complete a modest distance set (1000 total yards) broken by 100's on a set interval.

Step three - is to complete the required distance in less and less rest. 1:40 intervals become 1:35, then 1:30, then 1:25, then 1:20, then perhaps 1:15 or less for advanced age group swimmers.

The efficiency of all this is measured by heart rate. Once the athlete can work hard enough to elevate their heart rate into the 180-210 (per minute) range, then we measure the decrease in heart rate over weeks/months as they swim at the same speed, over the same distance. OR, swim faster, on the same rest and the same elevated heart rate. but our goal, first of all is to measure the constant intensity of our swimming (our speed) and seek to do it "easier" (fewer heart beats per minute.)

A look at any practice will reveal that there is a WIDE range of aerobic ability. By necessity, athletes will "fail" to hold an entire set....failure is good! -- it means that they are working to their maximum capacity. If they can "make" the first 4 of a set of ten, their next goal is just to make 5.....then 6, then 7. etc. You can't make progress without pushing to failure! The trick is to learn to work hard enough to "fail" further down the road of hard work, each time.

In a nutshell, that's Aerobic development. Volume, then constant speed at constant interval, then decreased interval and increased speed.

On Holding Children Accountable

By Guy Edson

A recent article, “Self-Esteem Lie” by Laura Caler, elicited a number of replies from coaches. To sum them up: “holding children accountable would be a lot easier if parents would take a step back and allow them to succeed and fail on their own.”

Coaches love to coach accountability and responsibility. They know it leads to better performances. But more importantly, and every coach will tell you, coaching life skills is every bit as important as all the swimming stuff.

One former coach writes, “I am now in management and I can see that the younger people entering the workforce who have not been allowed to fail on their own, who have not received negative corrections, or who have been otherwise protected from negativity to their self-esteem are difficult to manage. I don’t have the time or the budget to coddle them. I would rather work with people who are able to take the corrections and develop into better employees.”

Unfortunately, a coach’s ability to teach accountability is often interfered with by the parent.

A school psychologist writes, “I get all sorts of parents who are in denial about the problems of their children. I have parents calling me asking to have their children retake ADHD testing so that their child can be treated differently and not have to follow the same rules – even though their children are perfectly normal.”

A coach told me about the time he gave a warning to a swimmer who was late getting in the water for practice even though he observed him at the pool 30 minutes early. His warning was that on the next occurrence he would dismiss the swimmer from practice for the day. That evening he received a phone call from the irate parent telling the coach how difficult it was to arrange the transportation for getting the child to the workout and if he ever dismissed the swimmer from practice for ANY reason he would have to answer to the Board of Directors.

Another coach related to me the time at a swim meet when a swimmer was upset over her performance and asked “What can I do to get better?” The coach replied that coming to practice on a consistent basis would be the most important thing she could do. The father cornered the coach during a rare break time for the coach at the meet and demanded he apologize to his daughter for making her feel badly. She was “involved in many activities and was making as many workouts as she could” and her lack of improvement was the responsibility of the coach.

These are extreme (but not uncommon) denials of a swimmer’s personal responsibility.

What is a coach to do? Here is an answer most parents do not want to hear: The coach will learn to coach those who are responsible differently from those who hide from responsibility. One coach writes, “We have to pick and choose who we are honest with these days. It isn't a matter of style but more a matter of who the parents are and their style. I have basically identified the swimmers I can be more honest and direct with and the ones I can't be that way because of their parents. In my group of Juniors I have one swimmer I can't be honest with. I just say, "Good job" and that's it. When he swims poorly and the parent wants to know why he is swimming poorly, I tell will tell her my opinion but I know it is not something I can say to the swimmer without catching her wrath. So, at practice, I don't give him the full benefit of my coaching. For some others, however, they are all for me pushing their kids and being up front and honest with them. So, I am. And they respond. Some of the kids get a lot out practice because they get the full benefit of my coaching. Others do not because I have to hold back and only tell them what their parents allow them to hear. And when the kids who are getting all of the coaching do well, which they are, the other kids say, "Why are they doing better than I am?", the answer is pretty clear but I don't get to give them that honest answer either. And as these kids get older, they will be more and more handicapped because their parents will advocate for them, bail them out more, protect them more so that when they get to college or out in the working world, they will have no experience with any criticism or any failure because they have been protected or excuses have been made for them. In our case, or my case, because I can't be honest in my criticism on deck with some of them, they are not getting the complete coach. In fact, they are getting a very diluted dose of my coaching. So, how effective can that really be?”

What’s a parent to do?

Parenting expert Susan Brown of the Commonwealth Parenting Center in Richmond Virginia says to let your child fail. Brown wants parents to hold children more accountable for their mistakes and face the consequences. Learning to deal with failure, according to Brown, is part of becoming more responsible and accountable.

Helping Your Child Become a Strong Competitor

By Michael A. Taylor

Gymnastics Risk Management and Consultation

coacht@gym.net

Visit Michael’s Website at www.gym.net

You can help your child become a strong competitor by...

- Emphasizing and rewarding effort rather than outcome.

- Understanding that your child may need a break from sports occasionally.

- Encouraging and guiding your child, not forcing or pressuring them to compete.

- Emphasizing the importance of learning and transferring life skills such as hard work, self-discipline, teamwork, and commitment.

- Emphasizing the importance of having fun, learning new skills, and developing skills.

- Showing interest in their participation in sports, asking questions.

- Giving your child some space when needed. Allow children to figure things out for themselves.

- Keeping a sense of humor. If you are having fun, so will your child.

- Giving unconditional love and support to your child, regardless of the outcome of the day's competition.

- Enjoying yourself at competitions. Make friends with other parents, socialize, and have fun.

- Looking relaxed, calm, and positive when watching your child compete.

- Realizing that your attitude and behaviors influences your child's performance.

- Having a balanced life of your own outside sports.

Don’t . .

- Think of your child's sport participation as an investment for which you want a return.

- Live out your dreams through your child.

- Do anything that will cause your child to be embarrassed.

- Feel that you need to motivate your child. This is the child's and coach's responsibility.

- Ignore your child's behavior when it is inappropriate, deal with it constructively so that it does not happen again.

- Compare your child's performance to that of other children.

- Show negative emotions while you are watching your child at a competition.

- Expect your child to talk with you when they are upset. Give them some time.

- Base your self-esteem on the success of your child's sport participation.

- Care too much about how your child performs.

- Make enemies with other children's parents or the coach.

- Interfere, in any way, with coaching during competition or practice.

- Try to coach your child. Leave this to the coach.

SHOULD MY CHILD SWIM SUMMER LEAGUE?

By Priscilla Bettis

Lynchburg YMCA Swim Team

We’re in the midst of the summer league season as I write this, and we have quite a few athletes who compete for both their summer league team as well as our year-round USAS team. Should they? Sure! Simply put, it’s fun!

However, older children, injury-prone athletes, and national caliber swimmers need to approach summer league carefully. Pool time during summer league practice is limited, and older children would be better off evaluating their goals to decide whether competing with a summer league team supports the goals they hope to achieve. They might consider practicing with their year-round team while still competing at night for their summer league team. What’s more, summer league coaches appreciate less crowded lanes while teaching the novice swimmers.

Summer league races focus on sprint events, often not the focus of a year-round swimmer’s training. Additionally, summer league meets offer little warm up and warm down opportunities. This set of circumstances creates a situation where athletes are more likely to get injured. Responsible year-round swimmers would be wise to do a proper warm up at another pool and to stay after the summer league meet is over to do a thorough warm down when they can. Swimmers with a history of shoulder injuries should be especially wary about swimming summer league and should probably avoid it altogether if they are serious about being long-term competitive swimmers. It is imperative that those with shoulder problems continue with any exercises they have been prescribed to help keep their shoulders healthy throughout the summer.

National caliber swimmers need to keep their goals in mind when considering whether or not to join a summer league team. The intense demands on time and energy, and the dedication required to meet long term objectives, mean the distractions of summer league swimming will impair progress toward those objectives.

Summer league meets that last late into the night cause swimmers of all ages and abilities to be tired, and their training the next day will suffer. This means athletes should be scheduling naps, staying out of the midday heat, and taking care to hydrate and refuel.

Summer league swimming is often a youngster’s first introduction to our great sport. Having the more accomplished year-round swimmers compete on the same team creates a friendly bridge between summer league and more dedicated year-round swimming. Just make sure if your child decides to join in on the fun that he understands how summer league affects training, injury rates, and goal outcomes.

After considering all of the above, make sure you speak with your year around club coach before making a final decision.

“Teaching Hard Work to Parents As Well as Children”

By John Leonard

By John Leonard

The above quote came from the former President of USA-Swimming, Coach Jim Wood of the Berkeley Aquatic Club of New Jersey, in response to a question “what can we do to improve American Swimming?” at a USA-Swimming Steering Committee meeting last January.

Jim, as many of you know, is a 40 year plus veteran of the coaching scene, and owns his own pool and program and has been a leader in USA-Swimming for many years. He currently is President of USA-Aquatic Sports, the umbrella organization for the Aquatic Sports in the USA, as they report to FINA. He’s produced Olympians, National Champions, great age group teams and runs a highly successful swim business and swim school.

And his statement rang a bell with me.

I do talks for parents all over the world, as well as in the USA. And I “part time coach” my own team here in Fort Lauderdale, so I can stay current with all the things coaches face on deck in our sport. A considerable percentage of the parents that coaches deal with regularly have changed significantly from 10-20 and certainly 30 years ago.

I always ask parents what factors have led to their current success in life. Invariably, the majority have stories of hardships faced, challenges met, hard times overcome, on the way to a solid life and family, fiscal security or any sort of success you want to mention.

After these stories, a majority of parents say some variation on “boy, I don’t want my kid to have to go through that!”

And I am always floored. “you mean, you don’t want your child to experience the same formative experiences that you are describing as the ‘thing that made you what you are today’?”.

Invariably, they look at me blankly and then slowly it dawns on them what they are saying and the eyes go to the floor and you can almost hear an audible “hmmm….”

The natural response of any parent is to “protect” their child.

But let us not confuse “protect” with “shelter”. Children only really grow up under some pressure, some need to overcome something, the need to stretch, try harder, grow….in short, to GO TO WORK on something they care about.

The harder the work, the more satisfying the growth, maturity and individual strength created.

When we do something for our children that they are capable of doing themselves, we make them weaker. (not stronger) We want strong, independent children, yes? ……..Yes?

When we let children do for themselves, they learn to work for what they want.

Just like you and I did. And most parents did. Hard work is good for all of us.

Have confidence in your child and let them grow. They will prove themselves as strong or stronger than you. But they need you to “give them something” to get there…….

…the Freedom to do the hard work themselves.

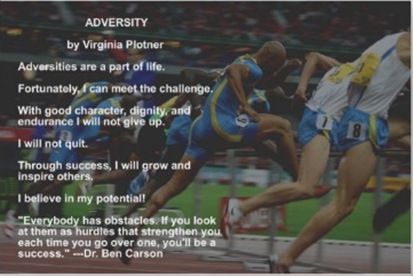

Forged By Adversity

Guy Edson, ASCA Staff

Guy Edson, ASCA Staff

I was following a school bus the other day when it stopped to pick up two middle school aged boys. Because of the framed glass emergency door in the back of the bus I could watch the two boys playfully tussling with each other as they made their way to the very last seat of the bus. Finally the bus began to move again – it seemed to take forever just to pick up two boys. I then thought back to my childhood days and riding the school bus. As soon as I crossed that white line on the floor at the front of the bus the doors closed and the bus sped off to the next stop, adding the dimensions of speed and bumps and movement to the normal tussling. It took balance and strength to make your way to the seat. Quite frankly, I sometimes didn’t make it to a seat without being deliberately shoved, or through my own clumsiness, stumbling and nearly falling. It was a challenge – but I never considered it as such. To me, it was “normal.”

Our school bus practices now are far more safe and part of a widespread effort to insure the safety and comfort of our children.

Who can be against that?

At the risk of getting some “what are you thinking” emails and maybe even a few cancelations, I am going to go out on a limb and suggest that our society’s collective efforts in protecting our children have, in subtle ways, removed “opportunities for falling down on the bus” and other failures. Failure is simply not allowed. Adversity is to be minimized.

Consequently, a healthy attitude toward failure and adversity is often undeveloped. A few years ago I was hired as the dryland training coach for a local high school. During a heavy weight lifting cycle I explained the concept of lifting to failure. (Lifting to failure, by the way, is an accepted and common practice in weight training. Widely written about and researched, it is the de facto method for improving strength.) Failure, as a concept, was so foreign to these high schoolers that they didn’t get it. Even when I demonstrated it, they still didn’t get it. Have we painted failure so darkly that no one gets the importance of it anymore?

hired as the dryland training coach for a local high school. During a heavy weight lifting cycle I explained the concept of lifting to failure. (Lifting to failure, by the way, is an accepted and common practice in weight training. Widely written about and researched, it is the de facto method for improving strength.) Failure, as a concept, was so foreign to these high schoolers that they didn’t get it. Even when I demonstrated it, they still didn’t get it. Have we painted failure so darkly that no one gets the importance of it anymore?

I am happy to report that some do still get it. Recently we interviewed a young person for an open position and when asked what she was really good at she replied that she was very good at failure. She explained that it was through failure that she learned how to succeed. How refreshing it was to hear that! (And yes, she was a former national level swimmer.)

Last week I attended a lecture by a former Navy SEAL who, after over 30 years of service, is now part of the SEAL training team. He explained the SEAL Ethos and what stood out to me was the phrase, “Forged by Adversity.”

“Forged by Adversity” is at the heart of what we do with our upper-level, older age group swimmers and all advanced senior swimmers. Adversity, however, is not something normal people deliberately seek. Most avoid it. All good coaches find that it is one of the greatest tools for shaping swimmers not only into great swimmers, but into future grownups with one of the best of all the life skills.

Adversity provides the opportunity to build determination, build confidence, build mental strength, give perspective, and to build physical toughness. Are these not qualities we want in all our children?

Adversity provides the opportunity to build determination, build confidence, build mental strength, give perspective, and to build physical toughness. Are these not qualities we want in all our children?

Arnold Schwarzenegger said, "Strength does not come from winning. Your struggles develop your strengths. When you go through hardships and decide not to surrender, that is strength."

And in swimming practice, adversity comes from sets, or possibly whole workouts, deliberately designed by the coach to make the athlete fail. The coach does that by creating a set where a combination of the distance, the intensity, and a low rest interval make it difficult if not impossible to make. There are many strategies and methods for doing this that go beyond the scope of this newsletter AND these strategies include a progression for how much adversity is presented at what ages, but the bottom line is this: Swimmers get better through a workout environment that offers the opportunity for failure.

And so, Parent, what is your role in all of this? I hope you refrain from seeking to protect your child from the adversity and opportunity for failure at swimming practice. To do so is to deny your child the opportunity for building the qualities described above. Instead, consider your role as the encourager. Encourage your swimmer to persevere, to break through, to come back the next day determined to work harder against the adversity placed there by the coach. Then enjoy and celebrate the moment when your child does break through. (And they will!)

Lessons From the Movie, The Sandlot

Allan Kopel

What makes for a great swimming race?

A fast start. Great entry. Explosive breakout. Correct stroke rate. Balanced splits. It is important to learn about, rehearse and refine all aspects of a race. It takes patience, persistence, focus, execution, correction, repetition, more correction and more repetition for each to become refined and part of one's race habits.

It all matters. They all play a role in a race. But how about also relaxing, trusting and having fun?

In the movie The Sandlot, the new kid, Scotty Smalls, is invited to play baseball with the other kids in the neighborhood; in The Sandlot. Smalls is excited but nervous since he never played ball nor had he learned how to catch or throw a baseball. When the first fly ball is hit his way, he stumbles trying to make the catch and then he runs the ball to the infield because he does not know how to throw it.

The best player in the group, Benny Rodriguez, is the one who invited Smalls to play with them. Benny takes a moment to reassure him. Benny is surprised when Smalls tells him he does not know how to throw a ball. Smalls is about to leave The Sandlot since he figures he cannot play well enough.

Benny says to him, “You think too much. I bet you get all A's in school.” (Not that that is a bad thing but it is a suitable comment in this scene - in this teachable moment).

Benny says, “Man, this is baseball. You gotta stop thinking. Just have fun.”

Benny then goes on to say, "I mean, if you were having fun, you would've caught that ball. You ever have a paper route?"

Smalls says, “I helped a guy once.”

Benny continues trying to teach him. "Okay, well, chuck it the way you would a paper. When your arm gets here (Benny gestures) just let it go. Just let it go. It's that easy."

Smalls then asks, "How do I catch it"

Benny: " Just stand there and stick your glove out in the air. I'll take care of it"

Learning to catch and throw, like learning to master swimming strokes and race strategy probably are a little more involved than that scene may suggest, but how about the idea of just trusting the moment and having fun with the activity; with the process and the doing?

Parents – keep nurturing your children's growth, keep supporting them in their positive endeavors (such as swimming) and keep teaching them valuable life lessons. But when it comes to sport specific skills and even the interpersonal dynamics of making friends and becoming part of a team, perhaps we can learn from the examples of Benny Rodriguez, Scotty Smalls and the kids from “The Sandlot”. Perhaps young people need and benefit from having their own space in which to learn , have fun, make friends, feel like part of something special, connect with people their own age and find ownership for their endeavors. We can all learn about helping young people by remembering how Benny Rodriguez helped Scotty Smalls play ball and feel like he belonged with the kids in The Sandlot.

Be well. Be safe. Stay fit. Keep it fun.

Allan Kopel

What Makes A Nightmare Sports Parent – And What Makes A Great One

Written by Steve Henson

Hundreds of college athletes were asked to think back: "What is your worst memory from playing youth and high school sports?" Their overwhelming response: "The ride home from games with my parents."

The informal survey lasted three decades, initiated by two former longtime coaches who over time became staunch advocates for the player, for the adolescent, for the child. Bruce E. Brown and Rob Miller of Proactive Coaching LLC are devoted to helping adults avoid becoming a nightmare sports parent, speaking at colleges, high schools and youth leagues to more than a million athletes, coaches and parents in the last 12 years. Those same college athletes were asked what their parents said that made them feel great, that amplified their joy during and after a ballgame.

Their overwhelming response: "I love to watch you play."

There it is, from the mouths of babes who grew up to become college and professional athletes. Whether your child is just beginning T-ball or is a travel-team soccer all-star or survived the cuts for the high school varsity, parents take heed.

The vast majority of dads and moms that make rides home from games miserable for their children do so inadvertently. They aren't stereotypical horrendous sports parents, the ones who scream at referees, loudly second-guess coaches or berate their children. They are well-intentioned folks who can't help but initiate conversation about the contest before the sweat has dried on their child's uniform. In the moments after a game, win or lose, kids desire distance. They make a rapid transition from athlete back to child. And they’d prefer if parents transitioned from spectator – or in many instances from coach – back to mom and dad. ASAP.

Brown, a high school and youth coach near Seattle for more than 30 years, says his research shows young athletes especially enjoy having their grandparents watch them perform. "Overall, grandparents are more content than parents to simply enjoy watching the child participate," he says. "Kids recognize that."

A grandparent is more likely to offer a smile and a hug, say "I love watching you play," and leave it at that. Meanwhile a parent might blurt out …

“Why did you swing at that high pitch when we talked about laying off it?"

"Stay focused even when you are on the bench.”

"You didn’t hustle back to your position on defense.”

"You would have won if the ref would have called that obvious foul.”

"Your coach didn't have the best team on the field when it mattered most.”

And on and on.

Sure, an element of truth might be evident in the remarks. But the young athlete doesn’t want to hear it immediately after the game. Not from a parent. Comments that undermine teammates, the coach or even officials run counter to everything the young player is taught. And instructional feedback was likely already mentioned by the coach. "Let your child bring the game to you if they want to,” Brown says.

Brown and Miller, a longtime coach and college administrator, don't consider themselves experts, but instead use their platform to convey to parents what three generations of young athletes have told them. "Everything we teach came from me asking players questions," Brown says. "When you have a trusting relationship with kids, you get honest answers. When you listen to young people speak from their heart, they offer a perspective that really resonates.”

So what’s the takeaway for parents?

"Sports is one of few places in a child's life where a parent can say, 'This is your thing,’ ” Miller says. "Athletics is one of the best ways for young people to take risks and deal with failure because the consequences aren’t fatal, they aren’t permanent. We’re talking about a game. So they usually don’t want or need a parent to rescue them when something goes wrong. "Once you as a parent are assured the team is a safe environment, release your child to the coach and to the game. That way all successes are theirs, all failures are theirs." And discussion on the ride home can be about a song on the radio or where to stop for a bite to eat. By the time you pull into the driveway, the relationship ought to have transformed from keenly interested spectator and athlete back to parent and child:

"We loved watching you play. … Now, how about that homework?"

FIVE SIGNS OF A NIGHTMARE SPORTS PARENT

Nearly 75 percent of kids who play organized sports quit by age 13. Some find that their skill level hits a plateau and the game is no longer fun. Others simply discover other interests. But too many promising young athletes turn away from sports because their parents become insufferable. Even professional athletes can behave inappropriately when it comes to their children. David Beckham was recently ejected from a youth soccer field for questioning an official. New Orleans radio host Bobby Hebert, a former NFL quarterback, publicly dressed down LSU football coach Les Miles after Alabama defeated LSU in the BCS title game last month. Hebert was hardly unbiased: His son had recently lost his starting position at LSU. Mom or dad, so loving and rational at home, can transform into an ogre at a game. A lot of kids internally reach the conclusion that if they quit the sport, maybe they'll get their dad or mom back.

As a sports parent, this is what you don't want to become. This is what you want to avoid:

- Overemphasizing sports at the expense of sportsmanship: The best athletes keep their emotions in check and perform at an even keel, win or lose. Parents demonstrative in showing displeasure during a contest are sending the wrong message. Encouragement is crucial -- especially when things aren’t going well on the field.

- Having different goals than your child: Brown and Miller suggest jotting down a list of what you want for your child during their sport season. Your son or daughter can do the same. Vastly different lists are a red flag. Kids generally want to have fun, enjoy time with their friends, improve their skills and win. Parents who write down “getting a scholarship” or “making the All-Star team” probably need to adjust their goals. “Athletes say their parents believe their role on the team is larger than what the athlete knows it to be,” Miller says.

- Treating your child differently after a loss than a win: Almost all parents love their children the same regardless of the outcome of a game. Yet often their behavior conveys something else. "Many young athletes indicate that conversations with their parents after a game somehow make them feel as if their value as a person was tied to playing time or winning,” Brown says.

- Undermining the coach: Young athletes need a single instructional voice during games. That voice has to be the coach. Kids who listen to their parents yelling instruction from the stands or even glancing at their parents for approval from the field are distracted and can't perform at a peak level. Second-guessing the coach on the ride home is just as insidious.

- Living your own athletic dream through your child: A sure sign is the parent taking credit when the child has done well. “We worked on that shot for weeks in the driveway,” or “You did it just like I showed you” Another symptom is when the outcome of a game means more to a parent than to the child. If you as a parent are still depressed by a loss when the child is already off playing with friends, remind yourself that it’s not your career and you have zero control over the outcome.

FIVE SIGNS OF AN IDEAL SPORTS PARENT

Let’s hear it for the parents who do it right. In many respects, Brown and Miller say, it’s easier to be an ideal sports parent than a nightmare. “It takes less effort,” Miller says. “Sit back and enjoy.” Here’s what to do:

- Cheer everybody on the team, not just your child: Parents should attend as many games as possible and be supportive, yet allow young athletes to find their own solutions. Don’t feel the need to come to their rescue at every crisis. Continue to make positive comments even when the team is struggling.

- Model appropriate behavior: Contrary to the old saying, children do as you do, not as you say. When a parent projects poise, control and confidence, the young athlete is likely to do the same. And when a parent doesn’t dwell on a tough loss, the young athlete will be enormously appreciative.

- Know what is suitable to discuss with the coach: The mental and physical treatment of your child is absolutely appropriate. So is seeking advice on ways to help your child improve. And if you are concerned about your child’s behavior in the team setting, bring that up with the coach. Taboo topics: Playing time, team strategy, and discussing team members other than your child.

- Know your role: Everyone at a game is either a player, a coach, an official or a spectator. “It’s wise to choose only one of those roles at a time,” Brown says. “Some adults have the false impression that by being in a crowd, they become anonymous. People behaving poorly cannot hide.” Here’s a clue: If your child seems embarrassed by you, clean up your act.

- Be a good listener and a great encourager: When your child is ready to talk about a game or has a question about the sport, be all ears. Then provide answers while being mindful of avoiding becoming a nightmare sports parent. Above all, be positive. Be your child's biggest fan. "Good athletes learn better when they seek their own answers," Brown says.

And, of course, don’t be sparing with those magic words: "I love watching you play."

-- Steve Henson is a Senior Editor and Writer at Yahoo! Sports. He has four adult children and has coached and officiated youth sports for 30 years. He can be reached at henson@yahoo-inc.com and on Twitter @HensonYahoo

SMOTHERED IN PRAISE

Are we hurting our children by constantly telling them how smart and great they are?

By Todd Huffman

For The Register-Guard

Appeared in print: Sunday, Oct. 3, 2010, page G1

“She’s so advanced!” beams the proud parent. “He’s just so smart!” boasts the doting grandmother.

So goes another day in the Lake Wobegon land of a pediatric office, where all the children are above average.

Not to disparage anyone, for who would contest the prerogative of kin to exult their beloved child? Would that all children be so adored.

Yet what happens when a child, since before she could talk, constantly hears that she’s smart? Does self-awareness of one’s smartness translate into fearless confidence later on? Or does it instill fearful hesitance to try new things, fearing failure?

Kids today are being raised in an age where self-confidence is everything. A positive attitude, not perseverance, is the answer to the riddle of success. At home and school, children are saturated with messages that they’re doing great — that they are great, innately so. They have what it takes.

Having been lauded from cradle to college for their greatness, too many leave the nest — if they leave at all — without the faintest idea of what greatness is, or what it demands. Greatness is always there and always theirs, and failure is always someone else’s fault.

According to a survey conducted by Columbia University, 85 percent of parents believe in the importance of telling their kids early and often that they’re smart. The presumption is that if a child believes he’s smart — having been told so, repeatedly — he won’t be intimidated by new challenges.

Constant praise is an angel on the shoulder, daily whispering the words of Al Franken’s Stuart Smalley: “You’re good enough, you’re smart enough, and doggone it, people like you!”

But a growing body of research strongly suggests that it works the other way around. Giving kids the tag of “smart” does not insulate them from underperforming. It actually might undermine their prospects of success.

Researchers long have noticed that large numbers of the smartest children severely underestimate their own aptitude. They lack confidence in their ability to tackle novel tasks. Smart children, to whom many things come very quickly, often give up just as quickly when things don’t.

Children afflicted with this lack of perceived competence adopt lower standards for success and expect less of themselves. They too readily divide the world into things they are naturally good at and things they are not. They pay rapt attention to the devil on the other shoulder, who shouts, “You’re not good at this!” Unless otherwise nudged or shoved into a new activity, too often they heed an internal warning to refrain.

Always having been praised for their intelligence, smart children often overlook or discount the importance of effort. My smarts are the key to my success, the kid’s reasoning goes, therefore I don’t need to put out effort. Expending effort is public proof that you can’t cut it on the strength of your natural gifts.

Researchers have measured the effect of praising schoolchildren for their intelligence (“you’re so smart at this”), as compared to the effect of praising them for their effort (“you must have worked really hard at this”). What is consistently found is that children praised for their effort subsequently choose harder tasks, while those praised for their intelligence choose easier ones.

Over and again, the “smart” kids took the easy way out.

The adverse effect of praise for innate intelligence on performance holds true for students of every socioeconomic class. And it knocks down both boys and girls — the very brightest girls, especially, are found most likely to collapse after failure.

Children praised solely and repeatedly for their intelligence are in effect being told the name of the game is to look smart, to not risk making mistakes and being embarrassed. Failure is assumed as evidence that they aren’t really smart at all.

Kids must of course be allowed to fail, and to learn from their failures. Let us do away with the hodgepodge of ribbons, pins and mass-produced certificates that commemorate everything but real achievement. No more banning schoolyard games that inherently produce winners and losers. If we are constantly rewarding mediocrity, how will children learn the difference between the excellent and the ordinary?

Brushing aside failure and just focusing on the positive is not being a good parent, caregiver or teacher. A child who comes to believe failure is something so terrible that the adults in his life can’t acknowledge its existence is a child deprived of the opportunity to discuss mistakes — and a child who therefore can’t learn from them.

Our job instead is to instill in children a firm belief that the way to bounce back from failure is to work harder. In other words, try, try again.

People with persistence — the ability to repeatedly respond to failure by exerting more effort instead of simply giving up — rebound well and can sustain their motivation through long periods of delayed gratification. Children who receive rewards too frequently and superfluously will not develop persistence; instead, they’ll quit when the rewards disappear.

Praise is important, just not vacuous praise. Researchers have found that to be effective praise needs to be specific, credible and sincere. Again, intelligence alone should not be praised. Effort, true skill or talent, insight, intention, patience, humility, tolerance, and receptiveness to constructive criticism — combined with a determination to learn from it — should be praised.

Instead of saying “you’re so smart,” parents and teachers should say, “I like how you keep trying.” Emphasizing and praising effort gives a child a variable that they can control. They come to see themselves as masters of their destiny. Praising natural intelligence removes destiny from the child’s control and provides no good formula for responding to a failure.

Kids should be taught that intelligence is something developed rather than innate. Kids taught thusly are more likely to make effort, to strive no matter the challenge. The concept of teaching kids that the brain is a muscle, and that giving it a harder workout makes you smarter, has been shown to greatly improve young school-age children’s study habits and grades.

We should be honest with our children if we feel that they are capable of better work. As parents and as teachers, we should not be there to make children feel better, but to encourage them to do better.

As parents, what’s the bottom line? Love your kids unconditionally. But unconditional love does not require offering unconditional praise.

While there’s no mistaking the allure of a life outlook in which you’ll make every basket, get every job and reach every star, teaching your children such an outlook does not prepare them for adulthood. And preparing our children for adulthood is our first and largest responsibility as parents.

We should not implant the absurd notion of, “Of course you can do it.” Success is not bought and delivered with the currency of happy thoughts. Success is earned through tenacity, patience, scholarship, sacrifice, self-discipline and due diligence.

The best slogan to live by and to teach our children isn’t all that inspiring, but it’s the truth: Expect failure, but keep trying. Joy is found in the striving. And with persistence, you will have successes.

Savor them and treasure them, for you’ve earned them through hard work.

“A Chance to Be A Hero Everyday”

By John Leonard

By John Leonard

“Prepare the child for the road, not the road for the child.”

“Everything we do for our children that they can do for themselves, makes them weaker.” (Lynn Offerdahl, great swimming parent in Fort Lauderdale, FL.)

One of the really sad trends in American society is parental “concern” that removes adventure and opportunity for growth from American children’s lives. Yes, the world is a different place from the one I grew up in, and many other people, as well. In that world, we were not constantly supervised by parents, and most often, were pretty much totally unsupervised by adults for much of the summer and after school hours as well.

We got cuts and bruises, we did “dangerous things” and looked out for one another. One of us usually had a reasonable degree of sense, and rarely did anyone get seriously injured, but we constantly did “daring” things that helped us understand the limits to our ability (and we regularly exceeded what we thought was possible.)

Contrast that with the average child’s life today.

In those days, we prepared every day for our future independent lives. And then, we rarely if ever came home after high school, and certainly never needed our parents to “support us” later in life. (Ok, I know, we can all point to exceptions to that….)

Today, not so much.

One of the very best parts of swim practice is that EVERYDAY, you get to test your “Hero” capabilities. In every program in the USA, the challenge can be that you will “do something you have never done before” and “be a hero” in that growth. Challenge is the essence of swim practice and the child learns to fail, pick themselves up, and try, try, try again until they succeed. Whether it’s an eight year old learning to dive off the starting block, or a 17 year old senior trying to complete that set of 100’s on 1:05, the opportunities for “hero development” are there. And if coaches don’t offer that, athletes don’t accept the challenge and parents don’t support and applaud that, we’re not showing much confidence in our young people.

One of the very best parts of swim practice is that EVERYDAY, you get to test your “Hero” capabilities. In every program in the USA, the challenge can be that you will “do something you have never done before” and “be a hero” in that growth. Challenge is the essence of swim practice and the child learns to fail, pick themselves up, and try, try, try again until they succeed. Whether it’s an eight year old learning to dive off the starting block, or a 17 year old senior trying to complete that set of 100’s on 1:05, the opportunities for “hero development” are there. And if coaches don’t offer that, athletes don’t accept the challenge and parents don’t support and applaud that, we’re not showing much confidence in our young people.

The days of 14 year old’s fighting off the Indians from Conestoga wagons crossing the great plains are gone. So are the 50’s when many of us took off at dawn and might not return home until after dark, with many “adventures” to grow from every day, but we can still go to practice, be completely responsible for our own success, and challenge ourselves to reach “hero status” every day.

And if you don’t practice and rehearse, you might really be clueless when you face that real-world challenge that all young people and adults do face, from time to time.

Heroes in practice prepare to be heroes in life.

All the Best, JL

John Leonard is the Director of the American Swimming Coaches Association. He has been on the deck coaching since the 70’s and has worked with developmental through Olympic swimmers. He has a vast consulting background in working with parents, athletes, coaches, officials, and administrators for over 40 years. He also runs the educational programs of ASCA that reach thousands of coaches all over the world.

“Put Your Hands Down”

By Guy Edson

Inevitably, when I am explaining then next swim set to age group swimmers the hands start going up before I have finished giving the instruction! I think to myself, “What is this? I haven’t even given you the whole story yet?”

Since I am an old guy, I can tell you I never saw that happened 30 years ago. This is a phenomenon I have noticed that is becoming progressively more common over the last 15 years. .